Memory Bug, 2022-23

Ulterior Gallery

Tsutaja has created a series of research-based, mixed-media works that address the history and culture of nuclear power. Her first solo show at Ulterior Gallery in 2017 was based on a narrative originating from the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and the related back story of infrastructure development in Japan from the postwar period on. Tsutaja’s second solo, in 2020, focused on the Japanese/American hidden history of the global hibakusha (nuclear victims) from the Manhattan Project to the present. Now, in Memory Bug, she further explores stories she has discovered within the histories of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Marshall Islands—specifically chronicling both first and second generation hibakusha.

In computing, a “bug” is a fault in the coding that causes a program to misbehave, produce an unexpected result, or crash altogether. But what does it mean to have a bug in our collective memory? Through her works, Tsutaja strives to record and share an account of nuclear history that has not been widely discussed. After tracking many oral descriptions of important moments from survivors and researchers, Tsutaja more fully grasped the ways in which memory and historical narrative are constantly being modified. While some documentation might have been intentionally rewritten or erased, other information may have just dissolved due to shifts in recording and media preservation technology. For Tsutaja, the politics of the post-war mass-media was one of the significant reasons why the real stories, including the painful reality of survivors, was not available in the public realm. The information that was publicly shared, and which determined the popular narrative and established the societal memory of those events, might have been affected by a “bug” from the beginning.

Japanese Sci-Fi movies (called tokusatsu films) and manga involve many coded ideas generated from the history of the nuclear weapon. Growing up, Tsutaja relished these forms of visual culture, not understanding their underlying connection to Japan’s post-war devastation. Tsutaja’s process, research and creation of a new narrative, revealed her rediscovery of the actual nuclear history hidden in manga and movies, such as Godzilla, Mothra, Astro Boy, Tetsujin 28, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and Akira. At the same time, Tsutaja’s image-making is deeply connected to old master painting and the history of art, as well as the politics and mythologies imbedded in those works. In choosing to produce a group of paintings for this exhibition, Tsutaja is constructing a dialogue between post-war Japanese visual history and mainstream art history through her re-interpretation of mass-media and subcultural imagery.

One example Tsutaja finds especially resonant is Mothra, which first appeared in the 1961 film produced and distributed by Toho Studios. Mothra is a colossal moth monster and became a recurring character in Godzilla movies. The film alludes to the Marshall Islands, using the nuclear experiments there as a narrative around which to build the story. Mothra is the main instance in which Tsutaja found a “bug.”

Tsutaja will exhibit seven densely configured new panel paintings and a series of small drawings centered on the histories of Nagasaki, Hiroshima, and the Marshall Islands. One sculpture, Secret Dioramas (2019), will accompany these works to draw attention to two of the most significant moments of WWII—the Hull note (the final diplomatic proposal before the attack on Pearl Harbor) and the Enola Gay (that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima). With Tsutaja's familiar wit and use of double meanings, the show’s title connects with the insect images she has widely introduced into her paintings, bugs computing, as well as information preservation and human memory, and insects which we tend to find grotesque and troublesome.

-from Press Release

Ulterior Gallery

Tsutaja has created a series of research-based, mixed-media works that address the history and culture of nuclear power. Her first solo show at Ulterior Gallery in 2017 was based on a narrative originating from the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and the related back story of infrastructure development in Japan from the postwar period on. Tsutaja’s second solo, in 2020, focused on the Japanese/American hidden history of the global hibakusha (nuclear victims) from the Manhattan Project to the present. Now, in Memory Bug, she further explores stories she has discovered within the histories of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Marshall Islands—specifically chronicling both first and second generation hibakusha.

In computing, a “bug” is a fault in the coding that causes a program to misbehave, produce an unexpected result, or crash altogether. But what does it mean to have a bug in our collective memory? Through her works, Tsutaja strives to record and share an account of nuclear history that has not been widely discussed. After tracking many oral descriptions of important moments from survivors and researchers, Tsutaja more fully grasped the ways in which memory and historical narrative are constantly being modified. While some documentation might have been intentionally rewritten or erased, other information may have just dissolved due to shifts in recording and media preservation technology. For Tsutaja, the politics of the post-war mass-media was one of the significant reasons why the real stories, including the painful reality of survivors, was not available in the public realm. The information that was publicly shared, and which determined the popular narrative and established the societal memory of those events, might have been affected by a “bug” from the beginning.

Japanese Sci-Fi movies (called tokusatsu films) and manga involve many coded ideas generated from the history of the nuclear weapon. Growing up, Tsutaja relished these forms of visual culture, not understanding their underlying connection to Japan’s post-war devastation. Tsutaja’s process, research and creation of a new narrative, revealed her rediscovery of the actual nuclear history hidden in manga and movies, such as Godzilla, Mothra, Astro Boy, Tetsujin 28, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and Akira. At the same time, Tsutaja’s image-making is deeply connected to old master painting and the history of art, as well as the politics and mythologies imbedded in those works. In choosing to produce a group of paintings for this exhibition, Tsutaja is constructing a dialogue between post-war Japanese visual history and mainstream art history through her re-interpretation of mass-media and subcultural imagery.

One example Tsutaja finds especially resonant is Mothra, which first appeared in the 1961 film produced and distributed by Toho Studios. Mothra is a colossal moth monster and became a recurring character in Godzilla movies. The film alludes to the Marshall Islands, using the nuclear experiments there as a narrative around which to build the story. Mothra is the main instance in which Tsutaja found a “bug.”

Tsutaja will exhibit seven densely configured new panel paintings and a series of small drawings centered on the histories of Nagasaki, Hiroshima, and the Marshall Islands. One sculpture, Secret Dioramas (2019), will accompany these works to draw attention to two of the most significant moments of WWII—the Hull note (the final diplomatic proposal before the attack on Pearl Harbor) and the Enola Gay (that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima). With Tsutaja's familiar wit and use of double meanings, the show’s title connects with the insect images she has widely introduced into her paintings, bugs computing, as well as information preservation and human memory, and insects which we tend to find grotesque and troublesome.

-from Press Release

|

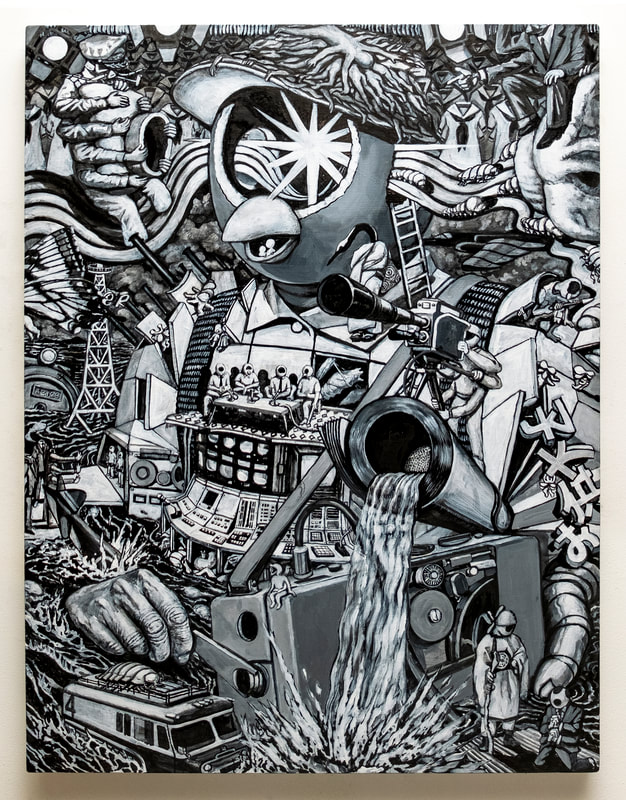

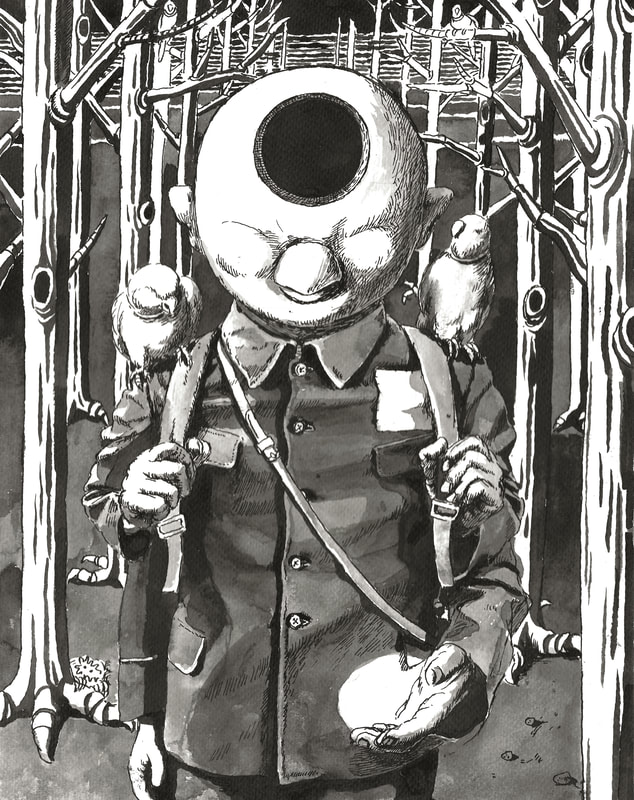

Memory Bug, 2022

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 25 7/8 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 65.7 x 4.1 cm) The giant robot in Memory Bug is a metamorphosis of Shunichiro Arai, a hibakusha exposed to radioactivity in Hiroshima City right after the atomic bomb explosion on August 6, 1945. He was thirteen. This robot signifies hibakusha's urge to pass their message to the next generation, as the 1945 A-bomb hibakusha are decreasing. The model for this robot is Tetsujin 28 (1956), a main character from a Japanese namesake manga. Arai's professional career was as a producer/director of radio and TV programs, and this influenced my image-making through the group of seven paintings. On the robot's left side, you see General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, who transformed radio broadcasting in Japan from the equipment of the Imperial General Headquarters into entertainment, such as jazz music programs and radio drama after the war. He also established The Code for the Japanese Press (SCAPIN-33) in 1945 to set up the framework for censorship. During the seven-year occupation, talking, writing, and researching about the atomic bomb were strictly forbidden. On the right, Kakuei Tanaka, Minister of Posts and Telecommunications (1957-58), sits on the robot's ear. Tanaka was the first politician who knew mass media's power and issued 34 commercial broadcasting licenses. Mitsuteru Yokoyama, an author of Tetsujin 28, is from Arai's generation. He designed this robot inspired by Frankenstein and the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. Tetsujin 28 was a secret weapon created by the Imperial Japanese Army at the end of the Pacific War. It was an evil figure when it first appeared. However, Yokoyama revised the character and switched it into a hero of justice with its popularity among children. Such modifications in the Japanese post-war storytelling point to the mass media's failure to record and convey the real stories of the war to the next generation. |

|

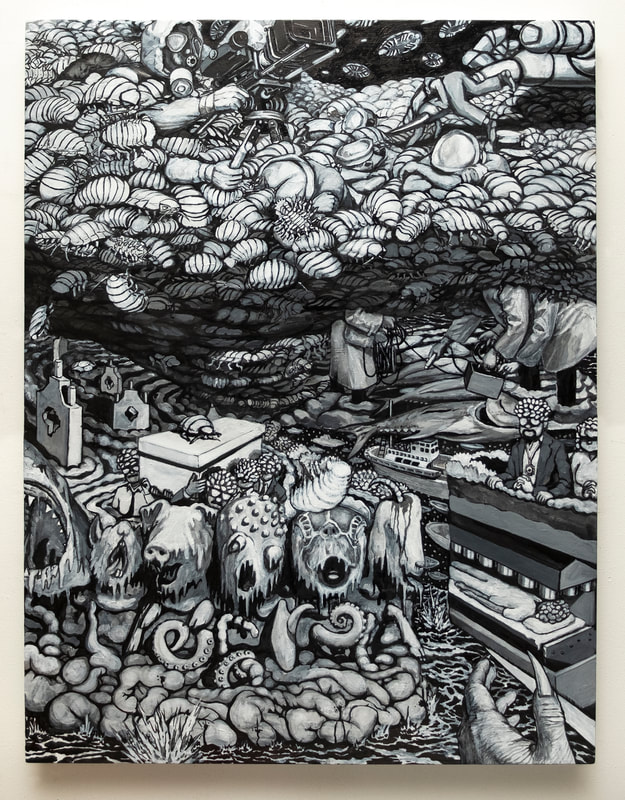

Bravo Cake, 2022

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 25 7/8 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 65.7 x 4.1 cm) Through Bravo Cake, I think about the craziness and ethics of nuclear bomb tests and their impact on life. The interview with Benetick Kabua Maddison, a nuclear activist from the Bikini Atoll of the Republic of Marshall Islands, is the source for this painting. The shape of the top part is from a mushroom/fallout cloud photographed thirty minutes after the detonation of Castle Bravo, the first hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954. It was one of 67 nuclear bomb tests that the United States conducted on the Marshall Islands. The U.S. did all their thermonuclear tests on the Marshall Islands and never on the mainland. As a result, two-thirds of the Marshallese population has migrated and most now live in the United States. They still suffer from nuclear-related health issues including premature deaths. On the right side of the painting there are health officials with a Geiger counter measuring radioactive tuna that were caught by 1,000 Japanese fishing boats. All of these boats were exposed to the fallout ashes from Castle Bravo, included the Lucky Dragon. I visualized this mushroom cloud as a cake. The idea is from a document photograph of a mushroom cloud cake that the Washington Post published in 1946. It was to celebrate Operation Crossroads at the Bikini Atoll, the first detonation of nuclear devices since the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. In the picture the mushroom cloud consists of Gusoku, the main bug character created from the idea I found in Mothra (1961) and Nausiccä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). The model for Gusoku is a carcass-eating bug that resides at the bottom of the ocean called Gusokumushi or Bathynomus Giganteus. The carcass-eating bug plays an essential role in the food chain in nature. But here, for the narrative of the nuclear world, I use them as metaphors for imperialism and dirty work. Humanity is at risk because mankind failed to control its fatalistic desires, and I painted an overwhelming number of Gusoku to signify that. Who are the people still eating this cake? |

|

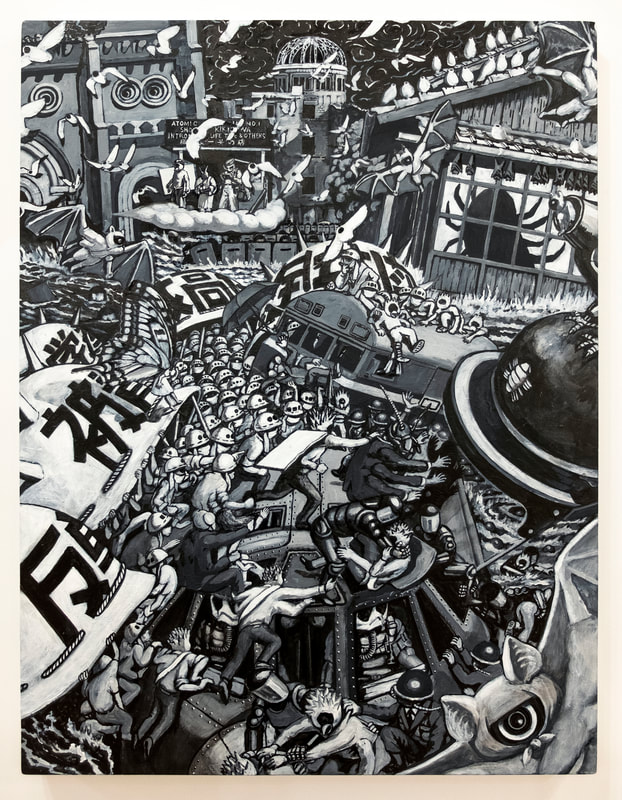

Peace Memorial Day, 2023

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 25 7/8 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 65.7 x 4.1 cm) I revised the symbolic images in the collective memory through "Peace Memorial Day." Based on an interview with Hatsue Kobayashi, a second-generation hibakusha from Hiroshima, I learned about the Hiroshima Riot that happened during and after the Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6, 1971. 14-year-old Kobayashi, represented as a swallowtail butterfly, witnessed the moment Mr. Ouchi, a hibakusha, caught the neck of Eisaku Sato, the Prime Minister shown as a roach, and shouted "Go Home!!" Sato announced the Three Non-Nuclear Principles in 1967, however he supported Vietnam War and made a secret pact to bring in nuclear weapons. People did not forgive this fork-tongued fellow and protested his visiting Hiroshima on the Atomic Bomb Memorial Day. The U.S. military stationed B-52s in Okinawa in 1968. 175 B-52s took off and headed to Vietnam from Okinawa between 1972 and 1975. In this painting the American B-52 bomber surfaced like Mechagodzilla (1974) from the bottom of the riot. Based on Godzilla as the model, Mechagodzilla was a weaponized robot developed by aliens who planned to conquer the Earth. The aliens launched Mechagodzilla from a secret underground base in Okinawa, which resonates with the history of nuclear weapons placed there in the 1950s. Between this riot and the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima preserved in its bombed-out condition, the Urakami Cathedral in Nagasaki is tilted. Despite the Atomic Bomb Archives Preservation Committee's hope to keep it, the effort of a Catholic Bishop led to its rebuilding with American support in 1959. Another tilted house called Nyokodo is Takashi Nagai's residence. He was a Catholic radiologist hibakusha and well-known for his bestseller essay, Bell of Nagasaki (1949.) GHQ allowed him to publish it by combining Tragedy in Manila, the GHQ's documents of the Manila Massacre. Nagai interpreted the atomic bombs as God's providence and preached to the survivors to accept the tragedy. A lesser-known fact about Nagai is that he was an extreme militarist during WWII. Many people now think of him as a symbol of peace. The shadow of the large Gusoku in his house points out this contradiction. The ninja-bat-shaped bugs with camera lenses on their faces fly into a crowd of headless robotic pigeons. They are the spirit of journalists who independently documented the history, including Kikujiro Fukushima. For this character, I referred to Francisco Goya's etching, A Way of Flying. |

|

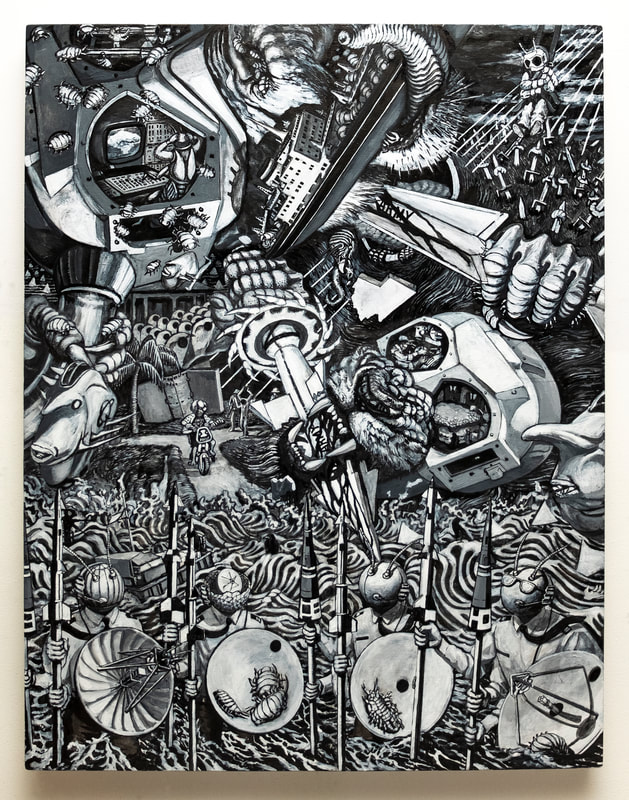

Test of the Gods, 2022

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 25 7/8 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 65.7 x 4.1 cm) The history of Kwajalein Atoll of the Marshall Islands is the subject in Test of the Gods. The interview with Greg Dvorak, an American historian of postcolonial Oceanian history who grew up in Kwajalein Atoll and now teaches in Tokyo, led me to make this image. As a child pictured on a tricycle, he is on the road of the colonization and battle histories between the Imperial Japanese Army and the U.S. Forces on the island. He is looking at the continuing U.S. nuclear missile tests at the Kwajalein Missile Range. The U.S. Army’s missile names, NIKE-HERCULES and NIKE-ZEUS made me associate this nuclear missile defense test with Greek mythology symbols. Hercules as a lion and Zeus as a bull. Both are wearing Gusoku helmets, a metaphor for imperialism. The bull is holding the Soviet Union’s ship in his tongue, which expresses the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962) and the TV news of the first Chinese thermonuclear test (1967) in his eye. In the lion’s eye you see Bravo Cake party scene and a Japanese engineer building a submarine. The four radar head men in front with shields and missile spears represent tribal members who believe the mythology of nuclear power and deterrence. There are bugs in their shields. The Gusoku helmet, resembling the Gundam suits and the U.S. nuclear protection gear, represents the relationship between fiction and reality. For this helmet design, I didn’t refer to Gundam suits but to the helmet design that the United States developed with a $7.2 million budget during the Cold War. They are to prevent the flashes of nuclear explosions from blinding the pilots of B-52 and B-1 bombers. As a result, it reminded me of Gundam suits. Gundam, an anime series aired in Japan beginning in 1979, unlike previous robot animations, it has a robot design that emphasized reality. Constructed by media mix, they became a mythical and magnificent space history with enormous information that fascinated children. Behind Dvorak, a naked Japanese prisoner captured in the Battles of Kwajalein and Roi-Namur (1944) is walking. These were amphibious invasions at two ends of the massive atoll that the U.S. planned carefully and won within 4 days by using overwhelming numbers of soldiers and weapons. In total, 332 Americans died in these battles, and there were about 8,410 killed on the Japanese side, a number which likely included a large number of the Korean conscripted laborers who had been building those Japanese bases. There was never any official record made of indigenous Marshallese people killed in these battles. There are still old Japanese military buildings all over Kwajalein Atoll even today. Layers of American concrete and asphalt all over the bases today still cover the graves of many of the soldiers who died during the war. The Marshall Islands, including Kwajalein, is an eternal battlefield theater. |

|

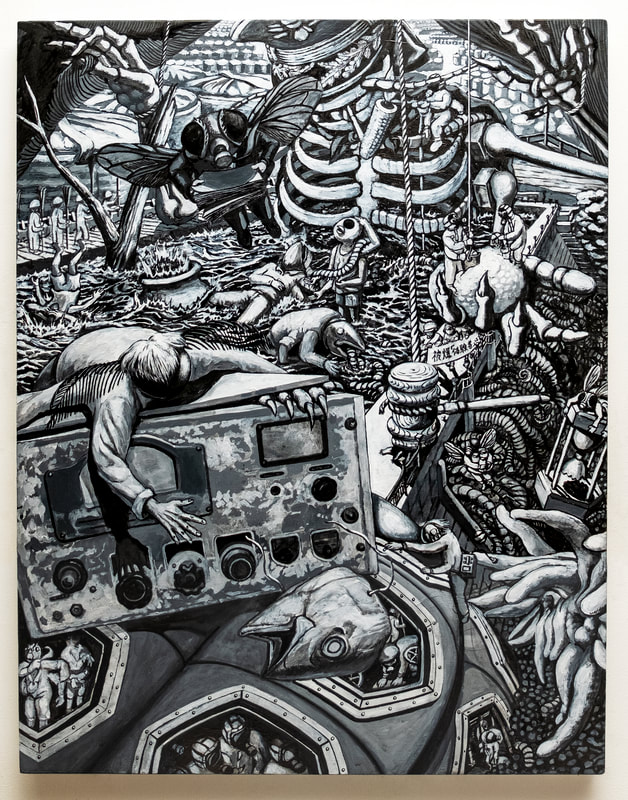

Captain Fallout, 2023

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 26 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 66 x 4.1 cm) In Captain Fallout, a giant skeleton opens a black rain curtain and invites a streak of light into the ship. He soaks himself in the water of Nishiyama Dam in Nagasaki, where the highest levels of radioactive black rain contaminated after the atomic bomb explosion in 1945. I interviewed Doctor Takaya Honda, a fly in the upper left corner, who carries lawsuit documents for his patients in his arms. His files include Takeshi Tsuru and Kazunori Watanabe, hibakusha living in the Manose district, a village with about 320 inhabitants. This area is much farther from the epicenter than the Nishiyama Dam. Despite their clear memories of the black rain and hair loss, the government has never admitted that it fell in this area for 78 years. In Hiroshima's "black rain" lawsuit, the 84-plaintiffs won to be newly certified finally as hibakusha in 2021. But plaintiffs in Nagasaki lost the case the following year. A giant gavel is shown in front of the Nagasaki plaintiffs. This painting depicts the history of fallout in which politics and the law have controlled facts and science. The large box in the front of the painting is the radio used by Aikichi Kuboyama, the chief communicator of the Lucky Dragon, who was exposed to the fallout from Castle Bravo in 1954. Kuboyama assumed the ashes were from the U.S. nuclear test because he saw a blast of light in the sky before the ashes arrived on his boat. He decided not to report to the home port, Numazu. Radio silence was an action to prevent the U.S. military from detecting the ship's presence. Kuboyama worked in surveillance in the Marshall Islands during WWII, so he feared the U.S. military's attack. They spent two weeks returning to the Akitsu Port at a slow speed. The crew on board experienced severe acute radiation symptoms, including headaches, vomiting, dizziness, loss of appetite, diarrhea, skin sores, blisters, and hair loss. After they arrived back in Japan, it developed into an international issue. Still, President Eisenhower held an intimidating press conference aiming to expand his nuclear arsenal. On March 26, he conducted another hydrogen bomb test in the Marshall Islands. Kuboyama died on September 23, and this tragedy triggered Godzilla’s production. In 1955, the Japanese government, about to introduce nuclear power from the United States, concluded negotiations with a two-million-dollar consolation payment and promised not to hold the United States accountable. Beneath the radio, a giant robot-like Gusoku crawls out of the dam where nuclear workers work. Captain Fallout sails into the world where pyramids of radioactive soil and waste containers line infinitely. |

|

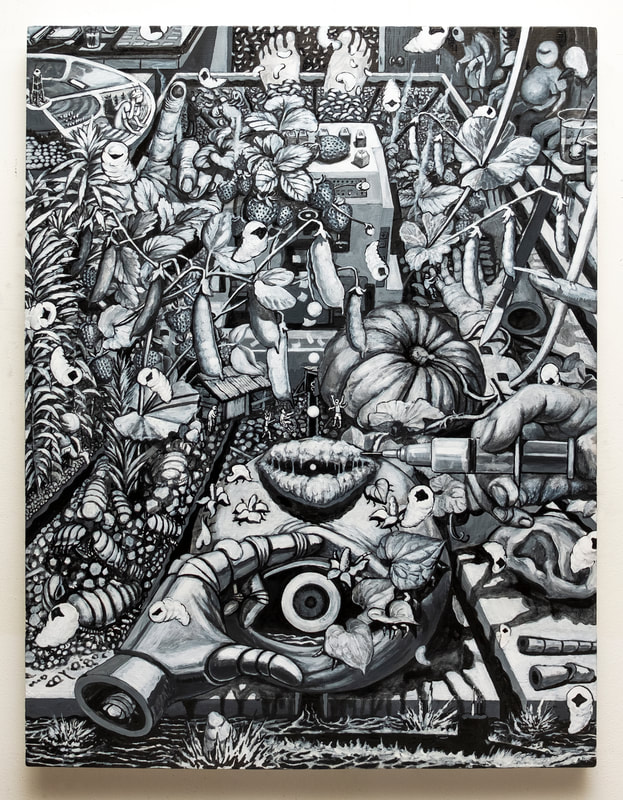

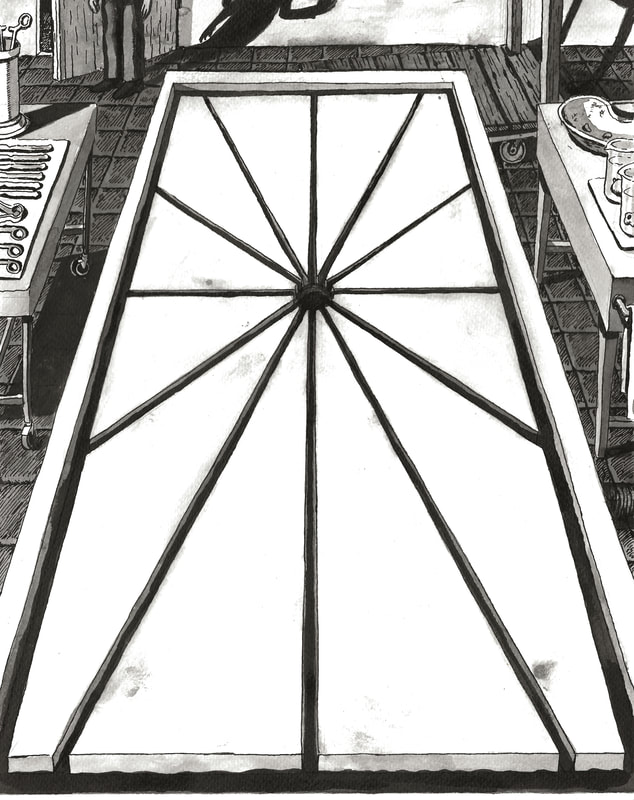

Atomic Garden, 2022

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 5/8 x 25 3/4 x 1 3/4 in (85.4 x 65.4 x 4.4 cm) Atomic Garden is about the experimental body based on the interview of Bun Hashizume, a poet who experienced the atomic bombing 1.6km away from ground zero in Hiroshima when she was fourteen. She received shards of glass in her body. Her lips swelled with pus, and she could not close her mouth because of pain for ten years. The treatment during that time felt life-threatening to her. The doctor injected cortisone into her entire lip with a thick needle; an experimental ACTH administration almost killed her. She did not trust the doctor who treated her. A pale male-faced Grim Reaper appeared in her dream when she had a high fever. Maggots rain is her expression at the sound of dropping maggots from the bandage of her uncle's arm. A single eye represents the deformed children people hid, and the museum also withdrew them gradually. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, established in Hiroshima and Nagasaki by a 1946 U.S. presidential decree, began researching the radiation effect on hibakusha. In the painting, Hashizume's body parts lie on a dissecting table at the ABCC. I found this dissecting table's design in Kikujiro Fukushima's infiltration report. Fukushima wrote, "(To drain blood into the sewage,) twelve shallow grooves are spreading radially at the same angle into other shallow grooves at the edge of the dissecting table from the hole in the center of the white marble." For 17 years, beginning in 1948, they dissected about 3,000 bodies annually, totaling 50,000. How did ABCC collect such a tremendous number of corpses? When hibakusha died, a black car came to pick up the body. In the center of the painting, a U.S.-made advanced microtome is shaving the organs to make microscope slides. They did this by boiling the dissected bodies and solidifying them with wax. The hibakusha's body was a specimen that suddenly appeared in large numbers. ABCC transported all samples and data secretly to the United States for military nuclear strategy against the Soviet Union; they were never for studying medical treatment measures for hibakusha. Hashizume distinctly remembered strawberries, snow peas, and pumpkins growing very quickly and big. This saved her and her family from starvation. A forest of mugwort grew so thick that a thief escaped into it. This witness led me to research the Atomic Gardening project in 1950, which was a part of the program Atoms for Peace. It is a form of mutation breeding plants by exposure to radiation. Although this project ended by the mid-1960s, the large-scale gamma gardens have improved many breeds until now. The resulting image of this painting resembles the apocalyptic post-World War III world of Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira (1982-90), where children with supernatural powers are subject to human experiments. Akira is the extreme one and the metaphor for nuclear power or the emperor that people cannot but want to control. Otomo named many characters as a parody of Tetsujin 28 as he considered the reinterpretation of Japan's revival after WWII. But Otomo expressed the war attractively with excellent details. This point is a significant change from the war generation creators. |

|

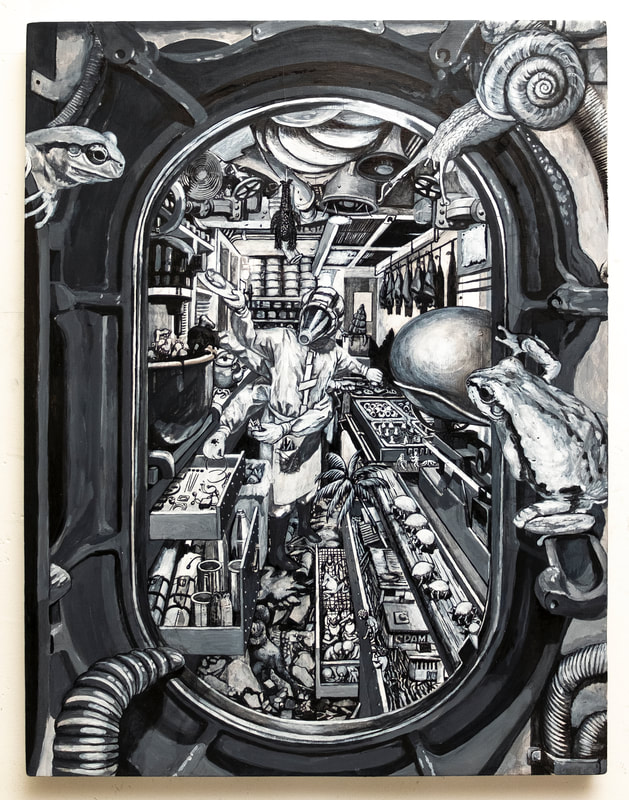

The Final Supper, 2023

Sumi ink and gesso on wood panel 33 3/4 x 26 x 1 5/8 in (85.7 x 66 x 4.1 cm) A lone chef in a radiation protection suit prepares The Final Supper in a troubled submarine kitchen. Submarines, one of the nuclear triads, suggest that many problems lie beneath the surface. The idea resonates with the worldly known masterpiece, The Last Supper, by Leonardo Da Vinci. I created this painting with this theme in Christianity and Western art history, thinking about what kind of menu would be suitable for The Final Supper, where somebody would be revealed as a traitor. This chef is Keiko Ogura, who was exposed to the atomic bombing 2.4 kilometers away from the hypocenter of Hiroshima when she was eight. She married Kaoru Ogura, a second-generation Japanese American born in Seattle in 1920. He served as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s Director and had a significant role in conveying the reality of the atomic bombing in English. He died suddenly in 1979 from a subarachnoid hemorrhage. After Kaoru's passing, Robert Jungk, the author of Atomic State, asked Keiko to interpret for his press conference in Japan. Since then, she has worked as a translator and messenger between hibakusha and foreign journalists and audiences. In this Submarine Kitchen, the chef prepares The Final Supper with ingredients charged with various metaphors, including Godzilla's tail and Mothra's egg. The corpses were the only place the survivors could walk barefoot safely as the collapsed buildings filled up the ground. The people in the container's soup show the story of the public bath where hibakusha with keloids couldn't go in for two years because of discrimination. The kettle in the kitchen indicates the one Keiko gave water to the survivors on that day. Everybody experienced what they didn't want to talk about anymore. The war orphans in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are 2,000 to 6,500. Parts of the hydrogen bomb B83 (80 times more potent than the Hiroshima bomb) that debuted in 1983, including their deadly plutonium cores, are kept in the drawer to be recycled. High-level radioactive nuclear waste and soil are in the bags and cans. The impoverished and ghetto Ebeye Island next to the Kwajalein, where many Marshallese are living until now. Keiko told me that it is important to express things that the museum does not display, and things nuclear victims hid in their hearts. The submarine door is from USS Bowfin during World War II, which I photographed when I visited Pearl Harbor. In 1944, the USS Bowfin torpedoed the Tsushima Maru carrying 1,700 evacuated civilians and children and killed 1,484. Two frogs, a snail, and an earthworm on the door frame are metaphors for disarmament and nuclear experts, historians, and philosophers. |

© 2015 Gaku Tsutaja